Hannah Beswick: the Manchester Mummy

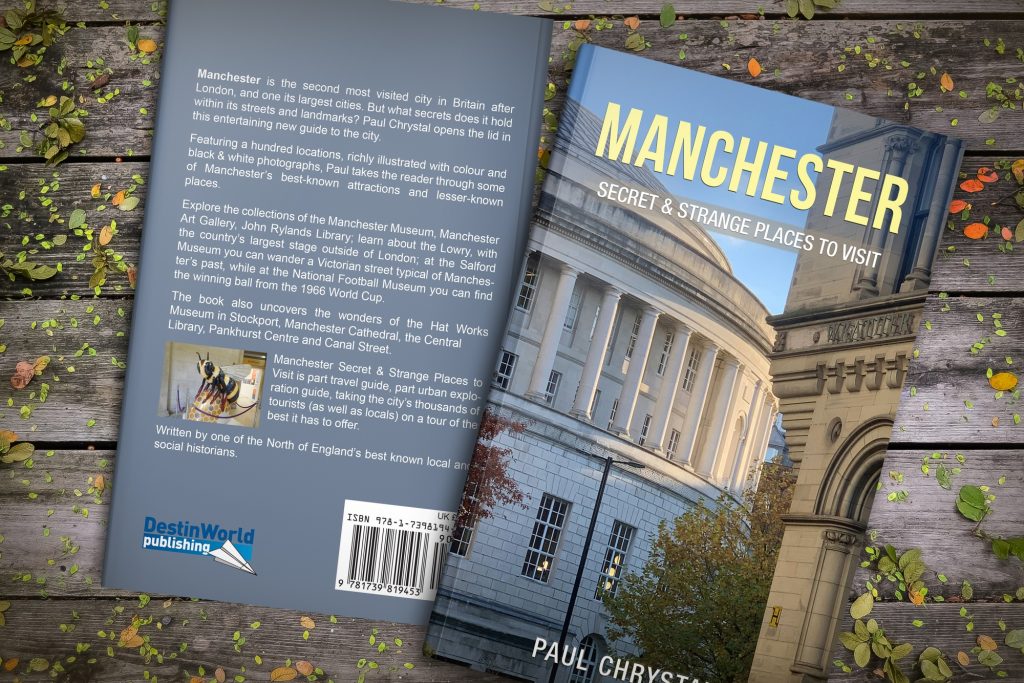

The fine city of Manchester is full of secret and strange places; it can boast scores of interesting residents from the past who have helped shape the city, and there are loads of artifacts and fascinating stuff just waiting to be pored over in our many fascinating museums and galleries. My book Manchester: Secret & Strange Places to Visit makes the job easier for you by collecting 100 or so of them in one book – ideal for dipping into at your convenience and planning your voyages of discovery.

Roughly very two weeks I’ll be blogging one or two of these for you; if you want to receive them regularly then make sure you bookmark our site, or visit the author at www.paulchrystal.com.

Hannah Beswick: the Manchester Mummy

Hannah died in 1758 and is buried in Manchester General Cemetery in Harpurhey; but it was a long and circuitous underworld journey which finally got her there in 1868 over a century after her demise.

Hannah (1688 – 1758), of Oldham, was a woman of means whose life was spoiled, to say the least, by her pathological fear of premature burial, or taphephobia; in laymen’s terms she was terrified of the prospect of being buried alive: she told her doctor this and set up what was the exact opposite of a DNR, ‘do not resuscitate’. Following her death in 1758 her body was embalmed and kept above ground, to be periodically checked for signs of life. The embalming probably involved a blood transfusion using a mixture of turpentine and vermilion.1

The body was then stored, aptly, in an old grandfather clock case in the house of Beswick’s doctor in Sale, Dr Charles White. Dead as she was she became a local celebrity, and visitors were allowed to view the corpse at Dr White’s house who eventually out-died her at which time the mummified body was bequeathed to the Museum of the Manchester Natural History Society, where she enjoyed yet more celebrity on display in the entrance hall there next to a Peruvian and an Egyptian mummy.

The “cold dark shadow of her mummy hung over Manchester in the middle of the eighteenth century”, according to Edith Sitwell 2. Some time later the museum’s collection was transferred to Manchester University (or Owen’s College as it then was) when it was decided in 1867, with the permission of the Bishop of Manchester, that Beswick should finally be buried since she had displayed all the symptoms of being dead for over a century and none of the symptoms of being alive . The funeral took place on 22 July 1868, more than 110 years after her death, in an unmarked the grave.

Manchester Secret & Strange Places to Visit

This wonderful new book is available now, delving into the curious places and stories of this city, along with Salford, Stockport and other surrounding areas.

Further reading:

Bondeson, Jan (1997), A Cabinet of Medical Curiosities, I. B. Taurus,

Bondeson, Jan (2001), Buried Alive: the Terrifying History of our Most Primal Fear, W. W. Norton & Company

Cooper, Glynis (2007), Manchester’s Suburbs, Breedon Books

Dobson, Jessie (1953), “Some Eighteenth Century Experiments in Embalming”, Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 8 (4): 431–441

1 The veins and arteries would have been injected with a mixture of turpentine and vermilion, after which the organs would have been removed from the chest and then the abdomen placed in water, to clean them and to reduce their bulk. As much blood as possible would then have been squeezed out of the corpse, and the whole body washed with alcohol. The next stage would have been to replace the organs and to repeat the injection of turpentine and vermilion. The body cavities would then have been filled with a mixture of camphor, nitre and resin, before the body was sewn up and all openings filled with camphor. After a final washing, the body would have been packed into a box containing plaster of Paris, to absorb any moisture, and then probably coated with tar, to preserve it.

See Zigarovich, Jolene (2009), “Preserved Remains: Embalming Practices in Eighteenth- Century England”, Eighteenth-Century Life, 33 (3): 65–104

2 Sitwell, Edith (1933), The English Eccentrics, London

Image: ‘The Premature Burial’ (1854) by Antoine Joseph Wiertz in the Museum of Antoine Wiertz in Ixelles, Belgium